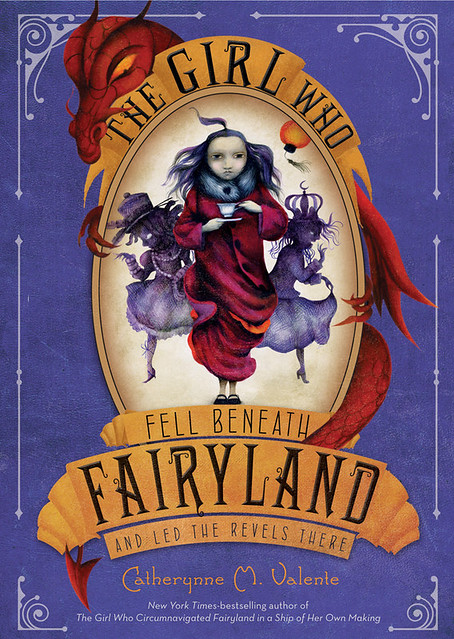

The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There

by Catherynne M. Valente

“She did not know yet how sometimes people keep parts of themselves hidden and secret, sometimes wicked and unkind parts, but often brave or wild or colorful parts, cunning or powerful or even marvelous, beautiful parts, just locked up away at the bottom of their hearts. They do this because they are afraid of the world and of being stared at, or relied upon to do feats of bravery or boldness. And all of those brave and wild and cunning and marvelous and beautiful parts they hid away and left in the dark to grow strange mushrooms—and yes, sometimes those wicked and unkind parts, too—end up in their shadow.”

September once went to Fairyland. She went on a quest, and lost her heart, and saved Fairyland from the evil Marquess. Now she is back home in Wisconsin, waiting for the day when her chance will come again. When it finally does, September returns to a Fairyland very unlike the one she left. And it seems to be mostly her fault. The shadow that she sold in Fairyland in return for a girl's life has taken over Fairyland-Below and begins to steal the shadows of those people above. The shadows hold the darker, more passionate, hidden desires of the bearer, and most of the magic as well. Fairyland is being drained of magic as September's shadow, The Hollow Queen, Halloween, "frees" the shadow people and builds up her kingdom below.

Last time, September was a heartless child. She was selfish, in the unapologetic way children are selfish, and her adversaries are external. She creates a boat out of her own clothes and hair and kills a fish with her bare hands. She wrestles her best friend to get a wish. She defeats a girl who is very like herself, or who she could have been. This time, September is older. She has a growing heart, as the book says, as she enters her early teens. Her adventures are internal, examining the idea of relationships through the eyes of deer people who see marriage as hunting and slavery. She struggles with shadows of friends she thought she knew. She wants to find the thing she is supposed to do with her life. She feels she has lost the wilder parts of herself since she has lost her shadow, but she equated it with growing older and more sensible. While the obstacles she faces are quieter and subtler than those in the first book, they touch the heart of one who feels she has lost her wildness from growing up.

Again, Valente creates a glorious world, this time Fairyland-Below. The shadow people, the Goblin Market, the Vicereine of Coffee and the Duke of TeaTime, the Forgetful Sea, the kangaroo-like miners who wear memories as a necklace, the Onion Man, the Prince sleeping at the bottom of the world, Quiet Magic (which I want to master), and the chilling, yet sad Alleyman who is responsible for stealing shadows for the Hallow Queen.

And as always September's lessons ring true for the reader, wisdom is dropped like breadcrumbs. Here are a few of my favorites:

- “For there are two kinds of forgiveness in the world: the one you practice because everything really is all right, and what went before is mended. The other kind of forgiveness you practice because someone needs desperately to be forgiven, or because you need just as badly to forgive them, for a heart can grab hold of old wounds and go sour as milk over them.”

- “I’m a monster,” said the shadow of the Marquess suddenly. “Everyone says so.”

The Minotaur glanced up at her. “So are we all, dear,” said the Minotaur kindly. “The thing to decide is what kind of monster to be. The kind who builds towns or the kind who breaks them.”

- “For though, as we have said, all children are heartless, this is not precisely true of teenagers. Teenage hearts are raw and new, fast and fierce, and they do not know their own strength. Neither do they know reason or restraint, and if you want to know the truth, a goodly number of grown-up hearts never learn it.”

- “Because it's my fault, you see. I did it. And you must always clean up your own messes, even when your messes look just like you and curtsy very viciously when what they mean is, I am going to make trouble forever and ever.”

- “Do you suppose you will look the same when you are an old woman as you do now? Most folk have three faces—the face they get when they’re children, the face they own when they’re grown, and the face they’ve earned when they’re old. But when you live as long as I have, you get many more. I look nothing like I did when I was a wee thing of thirteen. You get the face you build your whole life, with work and loving and grieving and laughing and frowning.”

Books Like This:

The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making by Catherynne M. Valente

Un Lun Dun by China Mieville